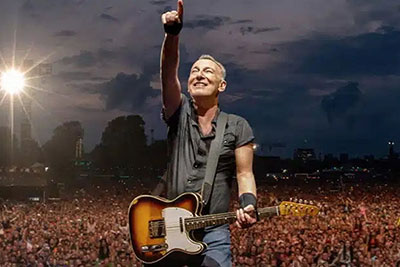

Nov

Bruce Springsteen - Cork and Kilkenny gigs sell out in 90 minutes

Kilkenny gig sell out in minutes as Bruce Springsteen fans snap up tickets. The Boss is coming to Ireland in May 2024

Jun

2014

Downstream of Kells bridge with its five arches. Photo taken from Mullins' Mill by Pat Moore.

by Sean Keane Kilkenny People

If you stand in front of Mullins Mill in Kells village and look in front of you at the bridge which crosses the Kings River, you are immediately struck by the five arches and behind them, a number of other arches, which visually are puzzling and rather beautiful.

From the Lacken side of the bridge, the eight arches (built in 1725) are there before you and it is impossible to see the five arches (built in 1775) on the other side.

From the Lacken side of the bridge, the eight arches (built in 1725) are there before you and it is impossible to see the five arches (built in 1775) on the other side.

The masonry is in danger of coming away at a number of points and it could do with being cleaned and weeded.

There is no scientific or technical reason for the mystery of the Kells eyes but it does have a mesmerising effect on you when you sit and gaze at it from the Mullins Mill side. The fact is that the first bridge with its eight arches was built when the bridge was constructed in 1725 and the second part of the bridge with its five arches was added when it was strengthened and widened in 1775, this was due to the phenomenal economic activity on the river at that time when the flour and flaxen mills dominated the landscape with Kells operating as a natural epicentre for all this activity.

Medieval town

And in recent months, aerial photography and infrared imaging and other photographic “tricks” have provided us with a huge amount of information about the original layout of the medieval town of Kells which was bigger than the present village and explains why it was accepted for a period as the capital of Kilkenny.

Simon Dowling has discovered the lost medieval town of Kells using 3-D models produced from an aerial drone:

You can look at the results of his work by logging on to http://aerialarchaeology.blogspot.ie/2013/09/kells-priory-co-kilkenny.html on the Internet.

He’s found the main street of the town and the burgage plots that run off the street - the town stretched from the bridge and motte to near the Priory that was founded by Geoffrey FitzRobert (William Marshal’s right-hand-man) in the late twelfth century.

It shows the importance of the bridge and why it had to be strengthened in 1775.

According to Kilkenny’s leading archaeologist, Cóilín Ó Drisceoil, Dowling’s work is a very significant archaeological discovery.

“We had glimpses of the village in the past from aerial photographs but now thanks to Simon Dowling and new technologies we have a much better idea of the full extent of the lost town of Kells,” Mr O’Drisceoil said.

It also confirms what older people in the village have been saying for years about seeing bits of streetscapes when digging foundations for various buildings (before the Planning Act of 1963).

These are exciting times for Kells but it seems to be lost on officialdom who have paid but scant regard to this most beautiful and tranquil of places.

And over the last few weeks it has been heartening to watch the amount of work by the Tidy Towns committee. It seems that most evenings during the summer, children receive kayaking lessons below the bridge and in front of Mullins Mill. It is a perfect place to swim and if you are feeling a little stressed or in need of some time out, come to Kells and sit looking at the mysterious arches of the bridge.

And as you sit on the wall of the bridge, you can see that it has done its job, Heavy machinery used to cut silage passes on one side while a car passes on the other with out any difficulty.

But Kells Bridge is much more than just a functioning piece of infrastructure.

It is at the very centre of life in Kells and in bygone days, after a big match or event, people would gather on the bridge in the evening time and discuss what ever big news was doing the rounds.

Even on Monday night, local Scot, Kenny McIvor was on the bridge, watching the children kayaking and 20 people must have stopped to chat with him over the space of half an hour. And Richard Delaney is right. “Some people,” he claims, “walk around Kells with earplugs in and don’t know how to say hello because of Facebook and twitter and that it wasn’t for the bridge and the local pubs the art of conversation could be lost completely.”

Nor is it possible to talk about the bridge without mentioning the 16 mills that once flourished along the King’s River between Callan and Ennisnag

And two of these remain in the shadow of the bridge, Mullins Mill which is now a milling museum with a cafe on the Ennisnag road side and a craft shop in the little building next to the mill and right by the river.

And on the front of the building is small plaque to the memory of the late John Sheridan (from November 2003) who did so much along with the rest of the volunteers that made up Kells Region Economic & Tourism Enterprise Ltd.

KRETE still does great work but needs state aid to get the mill fully operational again and make Kells a strong tourism destination.

And it is heartening that someone (a private citizen) is doing a huge restoration job on the commanding five storey Hutchinson’s Mill just above Mullins Mill and it will be fantastic when it is finished.

New life is being breathed into this historic building used as a working mill by the Mosse family Bennettsbridge up to the early 1990s

Appraisal

In the National Inventory of National Heritage, it appraises the bridge at Kells thus: “An elegant bridge of two distinct periods of construction representing a vital element of the transport legacy of Kells at either end of the eighteenth century: the resulting overlapping of the arches producing a pleasing rhythmic visual effect distinguishes the bridge in the context of the civil engineering heritage of County Kilkenny. Forming a pleasant landmark spanning the Kings River the construction in unrefined locally-sourced rubble stone with dressed accents displaying high quality masonry serves to integrate the bridge attractively into the surrounding landscape.

So when people visit the wonderful village of Kells, they are puzzled by the 18th century bridge which links the village and the priory to Callan, Ennisnag and Kilkenny city

The King’s River rises 25 kilometres upstream in the Slieveardagh Hills and feeds into the River Nore four kilometres downstream from Kells village.

Description

The first eight-arch rubble stone road bridge over the river was constructed in 1725. Approximately 50 years after, due to increased commercial activity, it was widened on the Ennisnag side with a stone parallel towards Hutchinson’s Mill.

The second bridge with five arches are of cut-stone with triangular cut-waters to piers, buttresses to north-west, and squared rubble stone coping to the parapets. On the other side, the eight arches are round with squared rubble stone voussoirs, and rubble stone soffits.

Few families have as long and as deep an association with Kells bridge as the Delaney’s who have lived 1oo yards from the structure for many generations.

Richard Delaney goes for a walk most evenings and always finds himself at the bridge looking down the Lacken flood plain, towards Callan-Newtown watching for mink or listening out for the sounds of nesting birds.

It has been a meeting place meeting for as long as he can remember.

“People from Newtown would come down and meet at the bridge or at the cross above and then you’d have the chat about whatever was going on,” he said.

He points to the Lacken below the bridge and explains that it is a flood plain full of wildlife and that he was told as a youngster that when the ice melted all those thousands of years ago after the glaciers shoved Ireland and Wales apart, the glaciers formed what is now the Lacken.

He has seen all sorts of animals in it but one gives him the shivers - the mink.

“They have killed a lot of fish, trout and a few salmon at Bradley’s Mill down river at the weir around spawning time. When he’s on the move you would see him darting,” Richard said.

He has a great affection for Mullns mill, and remembers well the last miller there, Paddy Mullins, explaining that his brother Sean (RIP) had worked for Paddy back the years.

“This bridge was so important to all those in the mill and all the people that it brought around,” he said with a hint of nostalgia in his voice.

Mullins was mainly a farming mill grinding flour - a functioning traditional mill and people around here have great memories of it and of the Mullins family who worked it for over 200 years,” he added.

The bridge, has according to Richard witnessed tragedy and he recalled the story how Mrs Hoban was killed after her bike it the pier of the bridge in the 1940s after coming down the hill.

Wildlife

The first house over the bridge on the Kells side of the river is the oldest surviving dwelling in the area and current resident, John Egan confided that it was once a bakery

He helps out at Mullins’ Mill and daily, he encounters a huge diversity of wildlife around the bridge.

In terms of flora and fauna, the Lacken on the Callan side of the bridge is a wetland paradise with all sorts of frogs and rare birds feeding there, including from time to time, swans.

For some reason, there is a colony of mink present her which are vicious. They are a non-native species and when they first came they were ferocious killers but in recent years, numbers have dropped but they are still particularly dangerous at spawning time.

This might because the stoat (a native species) has been seen there lately and the stoat will kill mink.

Like many other bridges, there are many, many bird types here like the kingfisher, mallard, water hen, and blackbird while the early summer heralds the arrival of the swallow. The wet grasslands of the Lacken are also home to visiting lapwing and snipe.

Of course bats are very common, especially at dusk.

In the course of doing this article, it became evident that all commercial life in Kells is dependant on the bridge.

And Simon Dowling’s aerial photography shots and the manipulation of them using state-of-the-art technology backs up the assertion.

It is impossible to speak about the bridge without linking it to the main mill for generations, Mullins Mill which provided employment for hundreds of people.

The first mill was built at Ennisnag in 1744.

It was destroyed in a huge flood and the family of French Huguenots moved to the present site in 1782.

This was a few years after the bridge was widened and strengthened and where it was perfect for a mill race to be completed or more likely to be restored.

Baron

The site is right before where the old castle gate, built by the first Baron of Kells, Geoffrey FitzRoberts, which would have led from the castle motte (at the back of Delaney’s) on to the old roadway and leading to what was then the new bridge.

It is also certain that Mullins Mill was built on top of an earlier mill placed there by Baron FitzRoberts.

In the charters for Kells village dating from 1204 and 1206, Baron FitzRobert grated fishing rights to the Priory from “his mill on the river which is before the gate of my castle of Kells and the land of Ennisnag.”

The first known miller was Patrick Mullins who married a member of the wealthiest family in the area, Eleanor Comerford in 1790.

The dynasty they created lasted until the 1960s with generations of Mullins’s living in the cottage on the left past the mill on the road to Ennisnag.

Mullins Mill was like many others a mirror image of what was happening nationally.

For example a flax mill was established beside the grain mill at Mullins mill and it thrived for years until the Act of Union in 1800 when the flax trade used to make linen) collapsed.

However, the grain mill continued and to give you an idea of the wealth in the area and the quality of the land, 80#% of the land around Kells was sown annually with wheat, barley and oats.

In 1965, the last miller, Paddy Mullins died and while a workman ran the mill for another year after that, it closed .

Wouldn’t it be fabulous to have a working mill on the King’s River where tourists and school children could go and watch different cereals being ground and see how flour is made.

If there is a better setting for such an enterprise, I don’t know where it is.

Thanks

Thanks to the staff at the Kilkenny city library and to Declan Mcauley and Damien Brett in the local studies section of the library at James’s Green. Thanks to Richard Delaney and to Coilin O’Driseoil.

Share this: