Nov

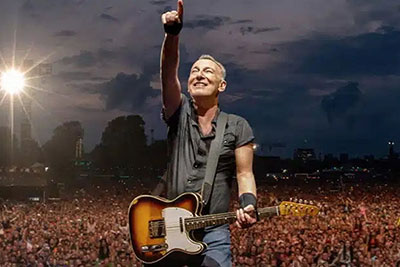

Bruce Springsteen - Cork and Kilkenny gigs sell out in 90 minutes

Kilkenny gig sell out in minutes as Bruce Springsteen fans snap up tickets. The Boss is coming to Ireland in May 2024

Nov

2012

Kilkenny fans go wild at the Senior Hurling All-Ireland Final replay in Croke Park. (Photo: Eoin Hennessy)

Published on Thursday 29 November 2012 15:00

Published on Thursday 29 November 2012 15:00

What motivates us to obsessively follow Kilkenny hurling, observing the same rituals and traditions each year? Why are young children familiar with the exploits of Eddie Keher, and why do they ascribe demi-god status to men like Henry Shefflin?

Inisights into these sorts of questions may be found in a new book by Carlow man Tom D’Arcy, who seeks to better understand the sports spectator, how sport shapes our lives and society, and the way in which it is intertwined with mythology and legend. Titled ‘The Sport Spectator –A Post-Modern Perspective: Sport as a Cultural and Societal Practice,’ the book evolved out of his PhD thesis, and is readable and accessible to even the most academia-shy reader.

From a black-and-amber point of view, the most fascinating element of D’Arcy’s research is his questionnaires of Kilkenny hurling fans, and the subsequent compilation and analysis of the data. He covers a range of topics, and includes many insights and comments from his interviewees.

He analysed two different groups of sports followers – Munster rugby and Kilkenny hurling. There were over 840 respondents to his surveys, ranging in age from 15 to 85.

Why Munster? Why Kilkenny?

“Over the past 10 years, they have been the two of the most successful Irish teams in their fields,” he says. “Kilkenny is just phenomenal.”

Indeed, his studies show that there are a lot of similarities between the two teams. When it came to supporters, however, there were some subtle differences.

While Munster fans prized ‘social interaction’ as a high priority, Kilkenny specatators were more likely to cite the skill and athleticism of their heroes, combined with ‘identity’ and ‘sense of place.’

“The sport of hurling,” writes D’Arcy, “is seen to epitomise characteristics which represent authentic ‘Irishness,’ these characteristics encapsulate well-defined sporting, political, religious and nationalistic sentiment. Hurling is an authentic traditional ‘Irish’ sport, and branded within a strong amateur status... In traditional Gaelic games culture, parish geographic boundaries are well defined, harbouring strong allegiance to ‘community,’ where a sense of place is inherent as an identity, and as a pride and passion demarcation.”

Community

That, it seems, is the GAA’s triumph – the volunteer aspect, the loyalty to one’s own club and parish. No highly paid mercenaries floating from club to club for the highest offer, no 19-year-old millionaires throwing weekly tantrums.

“This is why Kilkenny can do what it does – certain players set a standard and others aspire to it,” the author says.

“They don’t have to import players to produce quality. Adulation from spectators is a massive motivation for players to perform.”

So, too, the difference between two communities and two heroes – take Shefflin and an international superstar like Wayne Rooney. Both can play in a stadium in front of 80,000 people, but one might be behind you in the queue for the post office the next day, the other you will probably never even see in person.

There are over 325 million Manchester United fans in the Asia Pacific. Just 1% of the fan base even lives in the UK.

“The Kilkenny hurling star who has such an impact – he is touchable; it is stronger, deeper,” says D’Arcy.

“But with the Man Utd player, it is a much more artificial construction. You have a more imagined association.”

So do Henry Shefflin and Cu Chulainn have something in common, bar their unerring accuracy with a hurl and sliothar? This is the evolution of mythology.

D’Arcy examines a concept called ‘Hero Exemplar Construction,’ in which he puts posits that our modern ‘hero worship’ – from Willie John McBride to Christy Ring – is an evolution of the human being’s innate desire to keep alive the memory of the mighty deeds of past warriors and chieftains.

“The primitive desire to worship the magnificence of heroic individual performance and spectacle appears to permeate the intrinsic mindset of modern humans as it did in the ancient eras,” he writes.

There is always the danger that we over-romanticise the game, that we see things that are not there. But storytelling is an integral part of all sport.

“Young children sitting around the table, they hear of legends – of Henry Shefflin, DJ Carey, Paul O’Connell – and they see how highly these individuals are regarded by adults, the rest of the community, and they aspire to it,” says D’Arcy.

“They try to copy the characteristics of these people. It’s a form of vicarious transformation.

“So you see people wearing the names and number of their heroes on their jerseys. There is a huge need for hero symbolism, and athletes become almost demi-gods.”

D’Arcy differentiates between two different types of fans.

“There are two categories – the active sports spectator in the stand, and others who are huge fans but might have never been to a game.”

“They get a thrill from walking up a particular road, having a pint in a specific pub, sitting in the stand.”

Decades ago, there would be few women in Croke Park on All-Ireland final day. This has changed now, and there is a strong female contingent at most GAA matches.

“Sport reflects the changing trends in society,” he says. “There is an emergence of a new spectator category – ‘fashionable social engagement’.”

This, naturally, does not encompass all female spectators – nor does it pertain exclusively to women. There are, however, some interesting trends highlighted in the findings of D’Arcy’s questionnaires.

Bonding

He found that female spectator respondents tended to place greater emphasis on social interaction, belonging and community bonding between family and friends. Male respondents were more likely to highlight the camaraderie between players-performers and spectators, on physical prowess, and on emotion associated with tension, anticipation and competitiveness. Spectating, he says, “was cited as a platform through which unrestricted emotion expression could be engaged in without reprimand or censure.”

Some of the answers spoke volumes for why people have increasingly turned to sports spectatorship as vessel for their hopes and fears, for their emotions – and as a classroom for codes and values.

“The influence of the church has lessened as a graduating force, and to some extent sport has replaced it,” says D’Arcy.

“One Kilkenny mother, in the course of my research, said to me, ‘I can get no honesty from the Church, the State or the Government. I bring my children instead to matches to see honesty and genuine effort.’ It is a moral code that parents want their children to see.”

Tom D’Arcy is following on from his research in this field. His book ‘The Sports Spectator: A Post Modern Perspective’ is available in Stonehouse Books on Kieran Street in Kilkenny.

Share this: